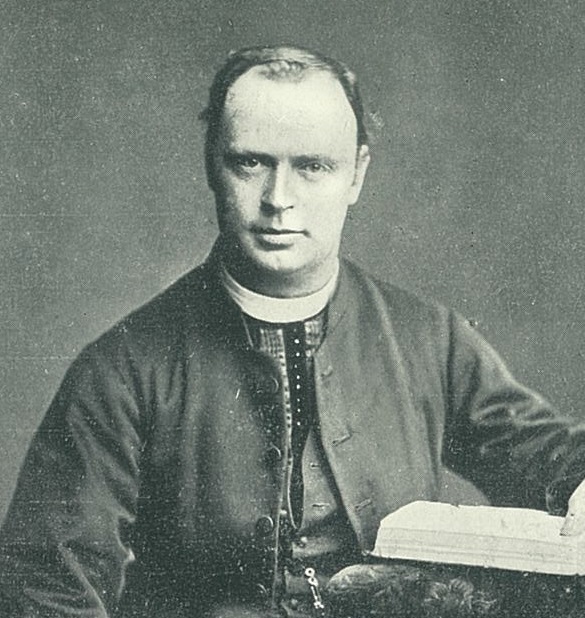

Micheál Ó Lócháin (or later Ó Lógáin), who was born in Curraghderry, Milltown in September 1836. Little is known of his youth. His father was a Lohan and his mother’s name was Hession. He went to school between the ages of nine and eighteen. This may well have been, initially at least, at a hedge-school run in Curraghderry by a teacher named Martin Doyle. Ó Lócháin remembered that while there, he was taught to memorize the bilingual catechism produced for the people of Tuam by Archbishop MacHale. He was a schoolmate in his youth of William Joyce, who was later parish priest of Louisburgh. One of his last teachers was Peter Duggan, an uncle of the future Bishop of Clonfert, Patrick Duggan.

Ó Lócháin emigrated and around 1871 he qualified as a teacher from St. Joseph’s School in Brooklyn, New York. He taught in St. Joseph’s for some time and it was at that stage that he began to earn a name as an activist for the Irish language. There were about 200,000 Irish emigrants then in New York, many of whom were native speakers. He began a Gaelscoil first in Jefferson Hall, at the corner of Willoughby and Adam Streets, and later at the corner of Atlantic Avenue and Court Street. He wrote many letters concerning the need to preserve Irish in the pages of the Irish World and the Brooklyn Citizen and founded the Brooklyn Philo-Celtic and Gaelic societies. In 1884, he helped found and became secretary to a national Gaelic Society for the US. It was around this time that he started the bi-lingual An Gaodhal and remained its owner and editor until his death in 1899. By 1897 he could boast that it had a monthly readership of around 1,500. It was in the pages of An Gaodhal that Raftery’s ‘Anois ag teacht an earraigh’ was first published. He also organized numerous social and cultural events, and in 1884 he helped produce a drama for stage at Steinway Hall, New York called ‘An Bard agus an Tó.’

After some years as a teacher he became an estate agent and auctioneer. Although unsuccessful, he attempted to get an ambitious scheme off the ground that would see half a million acres of land purchased in the American Mid-West to establish a settlement for a new Irish-speaking community made up of recent emigrants from Connacht; an Irish Zion of sorts!

Some years after his death, Tadhg Ó Donnchadha, editor of Irisleabhar na Gaedhilge and Professor of Irish in UCC penned Tuireadh Mhichíl Uí Lógáin in praise of the man from Milltown.

Tuam Herald, 23 May 2018